Desiderata (things desired): A monthly review of books recently read.

As a new year turns over, here’s a look back at what I read in 2019 that stirred my soul.

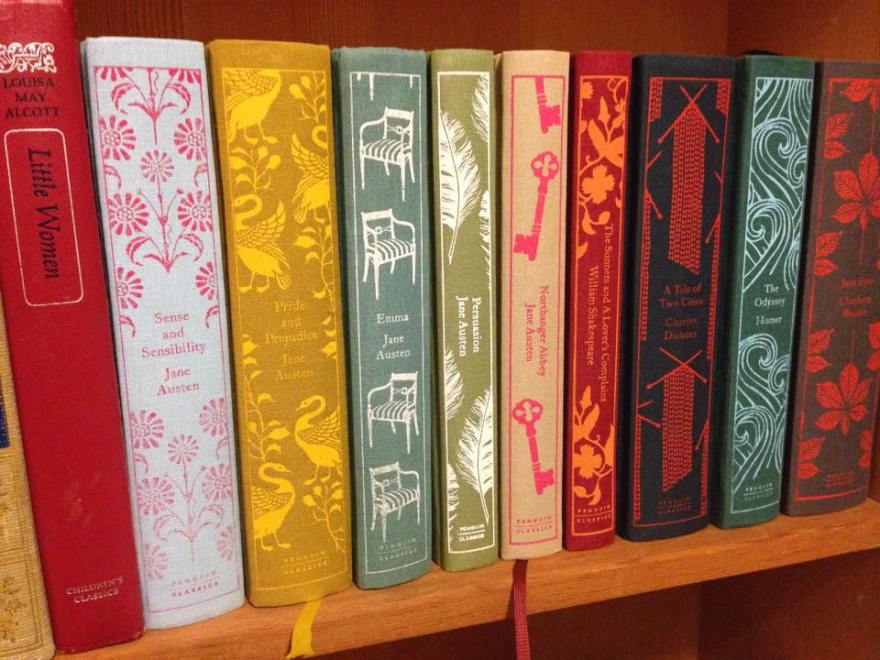

100 books read in 2019. Fiction, Creative Non-Fiction, Essays, not enough poetry. Many in the crime/mystery/thriller category as I continued to study the genre for inspiration for my own work. I hadn’t intended to read so much, prioritizing my limited time to finish the first draft of THE DEEP COIL. Which I did. It seems to naturally follow that the more I write, the more I read, the more room I must make in my life for words.

These are the books that wowed me, that I longed to press into every reader’s hands. Two categories, Fiction and Non-Fiction, no particular order. Clicking on the book will take you to my full review on Goodreads.

FICTION

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman

Somewhere around page 230 of Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine I began to ugly cry. Deep, shattering, heaving, snotty sobs. 5-star weeping. Eleanor Oliphant is definitely not fine. She’s a train wreck from which I couldn’t look away, until it became clear that I was looking at the mirror image of my most dreaded self. Alone Me. Lonely Me.

In a perfect balance between self-effacing humor and tender self-awareness, the author touches the live wire of our greatest and most private vulnerability: loneliness. Eleanor is a heroine of our times- the consummate misfit who makes us cringe —those of us who see our own misfit reflected in her.

I’ll Never Play The Hammered Dulcimer by Jan Hanson

The poems I love, that launch tiny tremors in my belly, close a warm hand around my heart, make my throat ache with unshed tears, my eyes sting with those about to fall, are made up of life’s small moments. A poet who captures the seemingly mundane and makes it shimmer with meaning is one who captures my attention.

At my grandmother’s house in Texas,

I wear an organdy pinafore and eat Sunday ham

and Kentucky Wonders off a pink-flowered plate,

swinging my legs under the ladder-back chair.

From IN TEXAS

Jan Hanson is just such a poet. In her debut collection, she captures the small moments of beauty and disappointment within the breathless steamroll of life — raising children, falling out of love, and stumbling into new passion, the grind of work when the call to create is so strong — with a voice that is as gentle and fierce as a hummingbird.

Once Upon a River by Diane Setterfield

On a quiet winter’s solstice night deep in the 1880’s, regulars huddle in the Swan — an inn tucked in the bend of the river Thames, not far from Oxford— swapping tales and sipping pints. The door slams open and into the shadowy room stumbles a man, his face battered, holding the lifeless body of a little girl. He is shown into a room where his wounds are tended by the local nurse, Rita. The little girl, drowned by the river that gives and takes according to its whim, is laid to rest in a cold storeroom until her body is claimed and her soul blessed into the afterlife.

And then a miracle occurs. The child takes a breath. She lives! But who she is and how she cheated death become the mysteries around which this rich, meandering, immersive story are wound.

The Far Field by Madhuri Vijay

In classic hero’s journey structure, Madhuri Vijay creates a deeply intimate story of a woman searching for personal identity in a place caught in political turmoil. As a child, Shalini has only a tacit understanding of the deep rift in the mountainous state of Jammu & Kashmir between the Hindu and Muslim populations. As a young adult, living so far away and so deeply in her own head, she pays little attention to the continued conflict. But once in Kashmir, she becomes embroiled in the turmoil, to catastrophic effect.

This is an astonishing debut. Vijay’s prose is gorgeous and evocative, poetic in its spareness, immersive in detail and content. Her themes and settings are epic and majestic, and yet this is a deeply intimate portrayal of friendship, betrayal, grief and remorse. The characters are rich with complicated histories and behaviors; the reader’s heart is broken open time and again by the people who guide Shalini into a better understanding of herself and the world.

The River is a brilliant tour-de-force thriller. Heller moves across the stunning landscape, at times brutal with careless treachery, at times heavenly with bounty and gentle ease, with breathless tension.

Ask Again, Yes by Mary Beth Keane

Francis Gleeson and Brian Stanhope meet as rookie cops in New York City and end up as next door neighbors in a small town just north of the city, raising their families and rising in their careers. Lena Gleeson is the perfect suburban mom, giving birth in rapid and delighted succession to three daughters. Anne Stanhope, however, is distant and cold, rebuffing all attempts at friendship and support as she recovers from a stillbirth, and when she becomes pregnant again with her son, Peter.

Told from the viewpoints of several characters over multiple decades, Ask Again, Yes examines mental illness, addiction, childhood trauma, family loyalty, and enduring love with grace and wisdom. Mary Beth Keane brings us into the hearts and minds of her characters and leaves us there, allowing us time to know them deeply, to develop the real ambivalence of empathy and fury, frustration and love.One of the most deeply moving novels I have read in a long time. Immersive, thoughtful, poignant and profound, Ask Again, Yes asks the reader to breathe with its characters, even through the worst of the pain, and not to look away at what we see reflected in their faces, even if it frightens us.

Big Sky (Jackson Brodie #5)by Kate Atkinson

We Jackson Brodie fans have waited what felt like an interminably long spell for our favorite private eye, in all his glib and glum glory, to return to the scene. But author Kate Atkinson has been rather busy in the interim, penning literary gorgeousness into Life After Life, A God in Ruins and Transcription. We’ll forgive her.

Our patience is richly rewarded with Big Sky, the fifth entry in the Jackson Brodie series. Although the novel could stand alone, fans of Jackson Brodie will shiver in recognition at the return of Reggie Chase, and nod heads with comforting familiarity at Julia’s throwaway affections (and affectations) and Jackson’s photographic recall of country and western lyrics.

The plot of Big Sky is a Venn Diagram of stories that contract until they become one, and Jackson is, of course, at the center of it all. “A coincidence is just an explanation waiting to happen” is one of Jackson’s favorite maxims, borrowed from some long ago episode of Law and Order. Kate Atkinson’s astonishing skill is not only to wink and nod at crime fiction tropes, but to render the plot so that coincidence feels utterly inevitable.

This novel slipped quietly on and off my radar more than two years ago when it debuted. I think I had it on my TBR list and removed it when I couldn’t get a copy from the library and Goodreads feedback proved greatly ambivalent.

A few weeks ago, the 2019 Dublin Literary Award was announced and Emily Ruskovich’s 2017 novel was the winner. This award made me sit up and take notice because the books are nominated for the Award by invited public libraries throughout the world. I love libraries and hold librarians in the highest esteem. The great percentage of short-list titles that are books I have loved makes this an award I pay attention to. So I thought I’d give Idaho another go.

And I’m so very glad I did (and thank you to my local public library for ordering in a copy at my request).

What begins as a literary thriller transforms into a quiet litany of grief, redemption, and the shifting nature of memory. The brutality of the narrative contrasts with the beauty of the language to create a captivating, unforgettable story.

The Secrets We Kept by Lara Prescott

Brilliant. Just brilliant. Everything about this novel, from its premise — a fictionalized account of the true plot by the CIA to thwart communism through “cultural diplomacy”— to its the multiplicity of perspectives, including the Greek chorus CIA typing pool, the haunted Olga Vsevolodovna Ivinskaya, imprisoned in a Gulag for her involvement with famed writer Boris Pasternak, the “Mad Men”-esque characters of Cold War Washington D.C., and their fashions, passions, parties — to the women who became spies, their stories all but forgotten by modern readers until Lara Prescott breathed life into their legacies — just sings and sparkles with verve and vibrancy.

The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

It is the early 1960’s and Jim Crow still holds sway in the South, even as monumental civil rights changes are sweeping across the land. Reform is slow to reach the Florida Panhandle and yet Elwood Curtis, a bright, shy, studious young black man raised by his officious grandmother, is determined to rise and shine, despite the heavy hands of racism holding him down. Even after he is sent away to the Nickel School for Boys for the non-crime of DWB- Driving While Black (in this case, Elwood is a passenger, blithely hitchhiking on his first day of college), he focuses his energy on achieving early release for exemplary behavior.

But the Nickel School for Boys, which houses white and black young men — separately of course — is not so easily endured. Punishment for any real or perceived infraction is torture and abuse, including solitary confinement, and even death.

Colson Whitehead based his fictional Nickel School on the Dozier School for Boys, a real house of horrors whose past was exposed in an investigative series in the Tampa Bay Times in 2014. For 111 years, from its opening in 1900 until the Dozier School for Boys was finally closed in 2011, boys as young as five years old were brutalized and dozens were murdered.

Lights All Night Long by Lydia Fitzpatrick(Goodreads Author)

And this was one worth having insomnia for. One of the year’s most moving (trembling, shaking) reads for me. I gasp in wonder and humbleness that Lights All Night Long is Lydia Fitzpatrick’s debut. Lights All Night Long is beautifully written, with characters cast in tenderness and compassion, landscapes that crackle with ice and throb with humidity, and an intricate, carefully woven plot that will leave you gasping at the end. But it is the relationship between the brothers Ilya and Vlad that will burrow into your heart, and break it, over and over. One of the year’s best. Now, let’s all get some sleep.

NONFICTION

What You Have Heard Is True: A Memoir of Witness and Resistance by Carolyn Forché

Carolyn Forché was twenty-seven when she traveled to El Salvador for the first time in 1978. Her searing, remarkable memoir is both a reportage of the brutal recent history of El Salvador, and the recounting of how an activist is created. During the twelve-year war, largely funded by American money and American military training, in this tiny, beautiful country, 75,000 were killed, more than 550,000 Salvadorans were internally displaced with 500,000 becoming refugees. The reverberations of the conflict are felt today, in the refugees who continue to flee poverty and political terror in Central America.

Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America by Beth Macy

Dopesick, centered in Appalachia where the opioid crisis began in the late 1990s with the release of OxyContin and where it remains the most virulent, delves deep into the circumstances of opioid abuse and addiction through intimate portraits of the victims, their families, the dealers, cops, and health care providers and activists. She explores every angle, revealing the blatant corruption of Big Pharma and the sickening failure of U.S. regulatory bodies to recognize and respond to criminal behaviors. Even the public shaming of the Sackler family and the lawsuits against pharmaceutical manufacturers, which roll through every day in the headlines now, don’t seem to sway average America from reconsidering what’s in their medicine cabinet. From Adderall to Ambien, we are hooked.

Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland by Patrick Radden Keefe

Right now, the only visible sign that you’ve crossed the border between the United Kingdom and Ireland is the change on road signs from miles to kilometers. In the twenty-one years since the Good Friday Agreement was signed in Belfast, signaling an end to the decades-long conflict known as the ‘Troubles’, the checkpoints have come down, the armed border patrols have been decommissioned, the observation towers are nowhere to be seen.

With Brexit looming, however, the visible division between the two countries may return, and with it, renewed calls to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and reunite it with the Republic. The prospect of reopening old wounds that are still so very close to the surface is so very real for communities on both sides of the border. Patrick Radden Keefe’s incendiary modern history of the bloody sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland could not be more perfectly timed. Say Nothing is part murder mystery, part political thriller, and all true. It reveals not just the cost of war, but the costs of peace.

No Visible Bruises: What We Don’t Know About Domestic Violence Can Kill Us by Rachel Louise Snyder

“Fifty women a month are shot and killed by their partners. Domestic violence is the third leading cause of homelessness. And 80 percent of hostage situations involve an abusive partner. Nor is it only a question of physical harm: In some 20 percent of abusive relationships a perpetrator has total control of his victim’s life.” From An Epidemic of Violence We Never Discuss by Alisa Roth, New York Time Book Review, June 7, 2019.

If you want to understand the horrific hold violence has on this country, this book will show the links domestic violence, or the more accurately-termed “intimate partner terrorism”, has to mass shootings, homelessness, substance abuse; why the #MeToo movement resonated so deeply; why it is so hard to generate commitment to laws and regulations that honor the safety of women in their own homes (yes, not all victims of domestic violence are women. Transgender and gay and lesbian partners are particularly vulnerable. Heterosexual men can certainly be terrorized by female partners in their own homes, as well. But 85 percent of intimate partner violence is perpetrated by men against women, so I, and the author, opt for the dominant model pronouns here).

This book is not just for those interested in the causes of and solutions to domestic violence. It is for anyone wishing to deepen their understanding of and compassion for the most vulnerable in this culture.

In the Dream House: A Memoir by Carmen Maria Machado

With her memoir and meditation on lesbian domestic abuse, In The Dream House, Machado reconstructs the rooms of her experience and memory to create a narrative filled with complexity and nuance.

Using vignettes that range from a chronological walk down the hallway of her recent relationship, to academic discourse on domestic violence between queer women, to a tapestry of self and sexuality woven from childhood memories, Machado experiments with form and tilts the function of memoir on its head. Each chapter offers a different narrative trope, a shift of the kaleidoscope through which to view her relationship and her responses to the growing doom she feels, recognizing the abuse even as she still loves the abuser.