Desiderata (things desired): An monthly occasional review of books recently read.

As I write, the good folks of Beijing, Auckland, New Delhi, Tokyo and Dubai have already bid 2020 adieu. There’s an extraordinary and epically bizarre laser light show happening from within a virtual Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris with music by the seemingly immortal Jean-Michel Jarre. Who knows what’s happening in Moscow or Montréal. Here in our quiet little corner, I’ve just remembered to put a bottle of bubbly in the fridge. Normally, I’d get in an afternoon nap in anticipation of making it to midnight and the evening’s festivities. Tonight. Hell. I just want to curl up with a good book and call it a year as soon as possible.

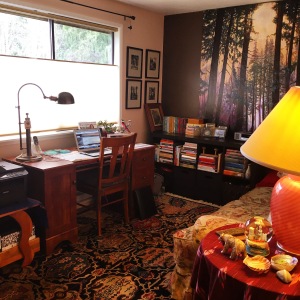

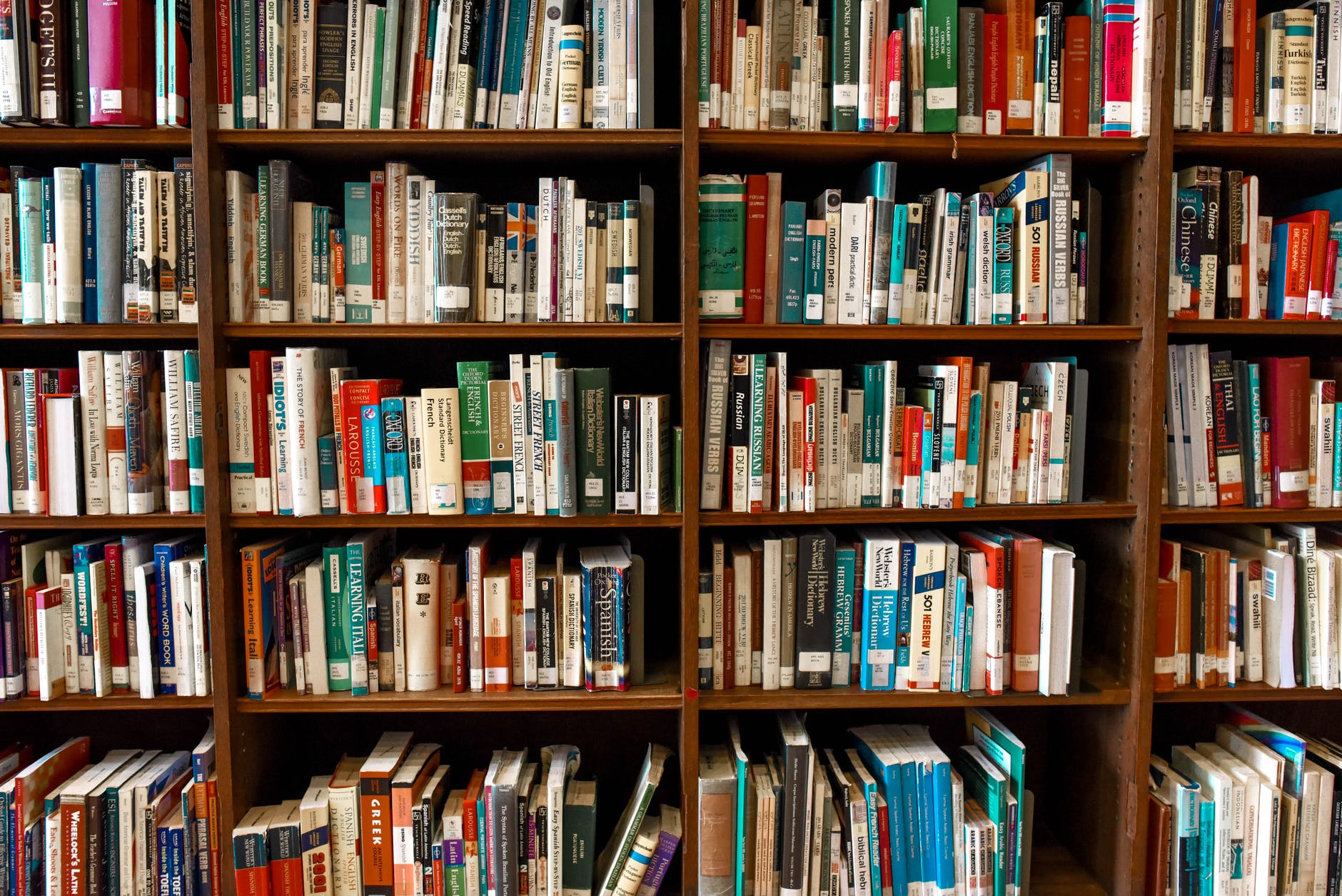

Reading came in fits and starts this year; there was a time in March and April when I found it so hard to concentrate. The brain settled down by late spring and I enjoyed rereading favorites from my own bookshelves as I waited for the library to reopen (to curbside pickup, natch. Haven’t actually set foot in a library since March… ) Summer ushered in a series of heavy non-fiction, but I was rested and ready. By fall I sought to escape again, binge-reading a bunch of mysteries that won’t make it to my top reads list, but they provided respite from the election-and-pandemic news cycle.

Here are the books — novels and non-fiction — I read this year that I’d press into your hands, if I could visit you. In order of when I read them, with snippets of my Goodreads review. Clicking on the cover will take you to the full review.

Before I let you go, know that you have my heart and hope for the year to come.

“For last year’s words belong to last year’s language And next year’s words await another voice.”

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett

Some Ann Patchett novels have taken my breath away (Bel Canto), others have left me less moved. The Dutch House succeeds for me because of the strength of its characters, who are allowed to grow and reach, creating a story in their wake. Tales of fortunes won and lost over decades, a panorama of post-war American culture, unhappy families, the ebbs and flows of marriage — these are all familiar themes that become fresh and urgent by the strength of Patchett’s Danny and Maeve and their voices. Told with reflective compassion, gentle irony, and vivid nostalgia for an America long-gone, The Dutch House is a deeply satisfying family drama.

Disappearing Earth by Julia Phillips

In Russia’s Far East, the Kamchatka Peninsula knifes between the Sea of Okhotsk and the Pacific Ocean. It is a 1250km-long blade serrated by volcanic mountains, honed razor-sharp by unrelenting cold, empty tundras, bears, wolves, and a history of violent encounters between Kamchatka’s indigenous people and mainland white Russians eager to plunder its vast natural resources. Julia Phillips chooses this perilous landscape as the setting for her mesmerizing, fierce debut, Disappearing Earth, easily one of the year’s top reads for me.

This Is Happiness by Niall Williams

The perfect antidote for the rush and anxiety of modern life and the superficiality of our connectedness, This Is Happiness reminds us of what it means to live fully, deeply, in the present, to experience our environment on its terms, without distraction. Narrated by Noe (short for Noel) Crowe as an old man looking back nearly sixty year to the summer his grandparent’s village of Faha, in Co. Clare, was hooked up to the electrical grid, This Is Happiness is a sumptuous, sublime and softly rendered tale of love, memory, grief and family.

Inland by Téa Obreht

This is a work of historical fiction, a panoramic western in the great tradition of Cather, McCarthy and Portis, but author Téa Obreht is too skilled a writer to be confined by expectations and conventions of genre. She writes with such urgency and empathy, with wonder for her story and compassion for her characters, that this reader was simply swept away in the moment, carried on the current of a brilliant narrative through a parched land where drops of water are as precious as flakes of gold.

Long Bright River by Liz Moore

Long Bright River is stunning. Billed as a thriller, it transcends genres. It’s a rich, dark, deep drama, intense with secrets and emotional traumas, atmospheric in setting, crushingly apt in storyline, and damn if I haven’t just found a new author to love. Like one of my other favorite reads so far this year, Julia Phillips’ Disappearing Earth, Long Bright River holds in its fierce wordfist the story of women exploited by culture and politics. It is about the forgotten and those we turn away from: the addicts and sex workers, strung out by poverty and slamming doors. Standard crime noir plot, but this is far from standard storytelling, this is a multidimensional and heartbreaking examination of a national epidemic and an intimate portrait of a family in crisis.

Mink River shimmers in the moonlight glow of lore and possibility, in a place that seems to be on the very edge of the world, of reality, even, sometimes, of hope. Doyle presents a hardscrabble logging and fishing village slumping off Oregon’s Coastal Range into the Pacific Ocean. It is a wet and whispery place, settled thousands of years ago by indigenous tribes who knew Paradise when it filled their bellies and souls. Now, remnants of those tribes still live in the fictional town of Neawanaka, carving stories into wood, into their children, into the forests and creatures which stand watch over its myriad inhabitants.

Oh, this beautiful, heartbreaking, astonishing book. There are not superlatives adequate in quality or quantity that do justice to a work of art that both opens the mind and fills the heart. Inspired by the real-life friendship between a Palestinian, Bassam Aramin, and an Israeli, Rami Elhanan, Apeirogon is a shimmering study of love and war. Each man lost a beloved daughter in the conflict that has torn apart this region since 1948. Smadar Elhanan was thirteen in 1997 when a suicide bomber carried out his mission as the teenager was out shopping with friends; ten years later, Abir Aramin was shot in the back of the head by a teenaged member of the Israeli army. Abir was ten years old.

The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

“We move through this world so lightly,” remarks a character in The Glass Hotel after she and her husband lose their life savings in a Ponzi scheme and are forced to take to the road, working seasonal jobs and living in an RV. This novel is about that lightness, that unbearable lightness of being, how we are barely, if ever, rooted in place. We revolve around the suns of chance, choice and circumstance and a shift of any, at any given moment, alters our worlds like that proverbial flap of a butterfly’s wings.

Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi

My head and heart are so full. I wouldn’t know where to begin writing a review. This is an extraordinary, necessary, vital book that is not just the history of racist ideas in America, it is the history of America. I read a library copy, but have since ordered my own. The references alone are gold, but Kendi’s comprehensive, thoughtful, lucid narration of American history is breathtaking. Be prepared to be enraged and enraptured. Please read this.

Greenwood is an epic saga that touches down in 1908, 1934, 1974 and 2008, before circling back to 2038. Christie’s sprawling storylines are centered on a few key characters and because we come to know these characters so well, the cross-sections are easy to follow. Not just easy — exhilarating. Despite the book’s length and density, Greenwood maintains a thriller’s pace, while not sacrificing depth of character or beauty of language. This is first-rate fiction: immersive, relevant and inspired. Highly recommended.

Proof writ large that a novel does not need to zap with plot twists or zing with Big Moments to be unputdownable. No exotic locales or dazzling characters, just the comfort of broken-in-blue-jeans characters that made me hug this book to my chest and sigh in the rapture of delicious, delightful storytelling.

This is a novel about longing. About knowing what you what- in Casey’s case, to be a writer, to be content with love, to have her mother back – and trying to make peace with what is left to you. It is also about agony of writing, how very hard and solitary it is, and how very pointless it feels to writers in their darkest and loneliest hours. And yet Lily King makes it seem effortless. This novel flows like a river, gentle and full in places, rushing, gushing, breathtaking in others, a collection of precise details, rich characters and beautiful, true moments that coalesce into a sublime whole. Surrender to this generous, loving, wry, compassionate novel knowing you are in the hands of a master.

I haven’t had a chance to write reviews of the two novels below, both historical fiction, by two of my favorite authors. Jess Walter writes of Spokane in the early 20th century- a rollicking tale of brotherhood and the labor movement in an up-and-coming frontier city. Emma Donoghue takes us to Dublin in 1918- three days in a maternity ward in a city ravaged by the flu pandemic-timely and tender. These are tales based on historical fact but graced with damn good storytelling. Add them to your list!